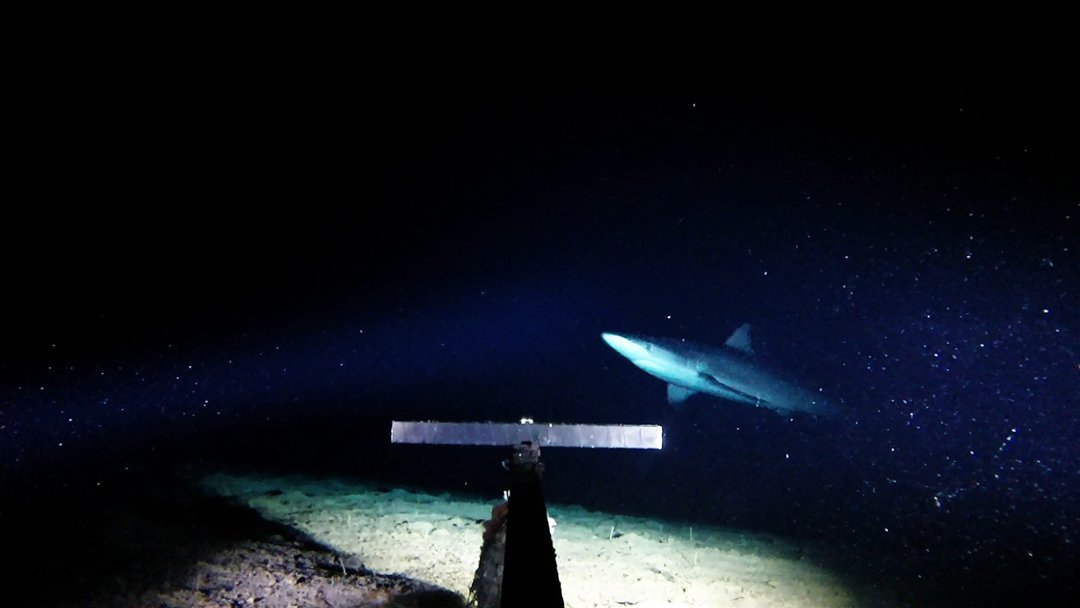

Night shark fever

Scientists are digging right down to the level of DNA to learn more about how to protect sharks. A new paper published by SOSF funded scientists Mahmood Shivji and Demian Chapman, led by lead author Rodrigo Domingues, shows how a better understanding of sharks’ genes can help us make big decisions about their management. Equipped with new information on the ancient history that this microscopic level of detail reveals, we can scale right up to improve future protection plans for these shark populations.

Understanding the “genetic structure” of shark populations has become very important for scientists. That is, learning more about patterns in an individual shark’s genes, can help scientists make assumptions about individuals in the rest of that population. This kind of information eventually helps to figure out how shark populations are distributed across the seas, which areas of the ocean are vitally important to protect, and informs how we should managing regions of ocean divded into manageable blocks called management units (MUs).

What’s the problem?

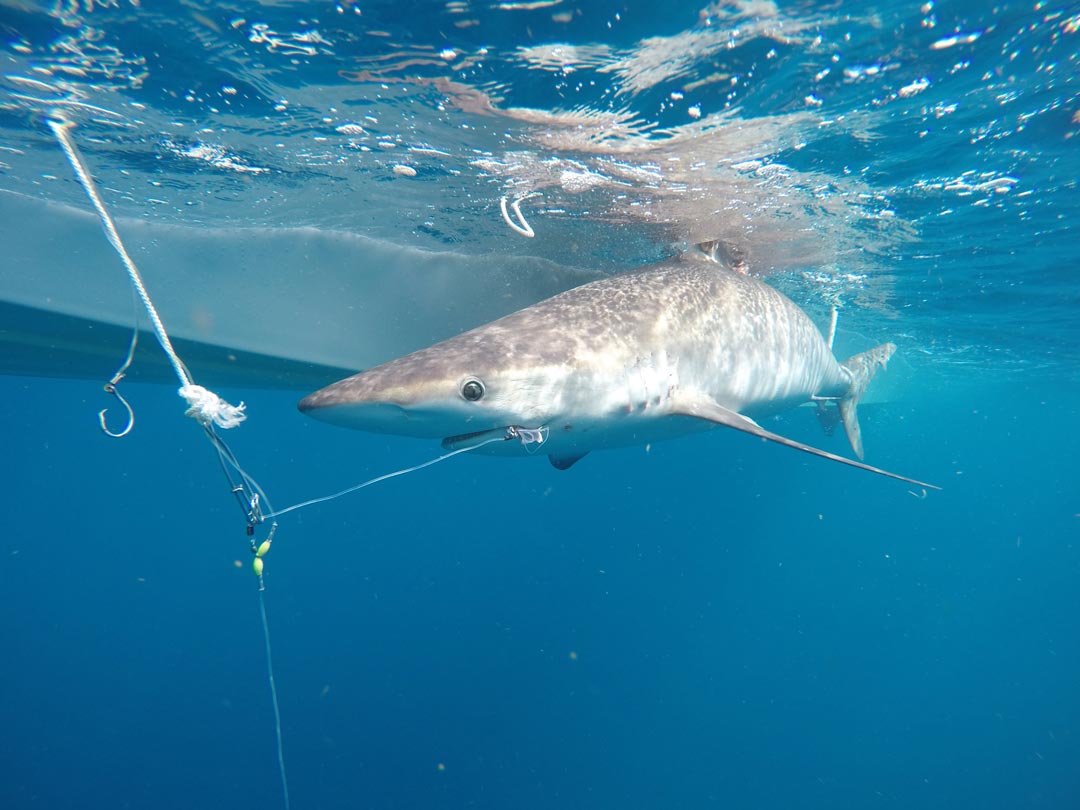

Night sharks (Carcharhinus signatus) are highly threatened, caught as bycatch by the longline fisheries that target swordfish and tuna. They are listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN RedList. There is no information on their genetic structure; that is, scientists don’t know about the genetic connectivity and diversity in night sharks (How many distinct populations are there? Are they connected across ocean regions? What’s their evolutionary history?)

What did scientists do about it?

The study ‘Genetic connectivity and phylogeography of the night shark (Carcharhinus signatus) in the western Atlantic Ocean: Implications for conservation management‘ was published in the journal Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems this year. Lead author Rodrigo Domingues, together with co-authors that include Demian Chapman and Mahmood Shivji, looked at the genetic diversity (the sum total of the genetic characteristics in a species), genetic connectivity (exchange of genes between individuals and populations), and phylogeography (the evolutionary history and genetic processes that explain where these sharks are found today) of the species throughout the western Atlantic Ocean.

What did scientists find?

Genetic diversity is low for night sharks in the Western Atlantic, based on results from both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA.

There seems to be evidence of restricted genetic connectivity between night shark populations in the western North Atlantic and the western South Atlantic. These populations are separated by at least 4150 km (tagged night sharks have been recorded swimming up to between 1000 km and 2000 km) so the isolation between populations seems likely due to distance, and there’s no evidence of panmixia (interbreeding between individuals in a population without restriction). The researchers think there might be at least two distinct breeding areas in the region for night sharks.

The phylogeography points to night sharks having evolved from a common ancestor that diverged fairly recently into two lineages.

What does this mean?

This kind of information helps us better understand how to manage these sharks’ populations. They’re currently grouped as one population by the IUCN and managed as such. However, this study suggests that the IUCN should make regional assessments of night shark populations.

In general, genetic diversity is linked to the capacity of a species to adapt to changing environmental conditions, or to respond to pressures. Low genetic diversity is troubling, particularly in a population that faces plenty of challenges, because the ability to adapt is low, and the likelihood of extinction is higher. Genetic diversity was lower in the unprotected night shark population in the western South Atlantic, than it was in the protected night shark population in the western North Atlantic. Overexploitation can drive lower genetic diversity over time, and ultimately threaten the resilience of that population.

To protect overall genetic diversity, we’d have to take into account the two lineages that diverged (it’s worth protecting both). The researchers recommend that night shark stock assessments and management plans are developed separately for the western North Atlantic and the western South Atlantic.