White Shark

Carcharodon carcharias

White sharks, or great whites, are the most iconic of all sharks. They are large and imposing, but surprisingly elusive, in part owing to their ambush predation techniques. They take advantage of low light situations (e.g. dawn, dusk, depth) to ambush unsuspecting prey, famously breaching (leaping out of the water) in some locations. They are also one of the few shark species to display endothermy, the ability to maintain a higher body temperature, which allows them to sustain higher speeds while hunting.

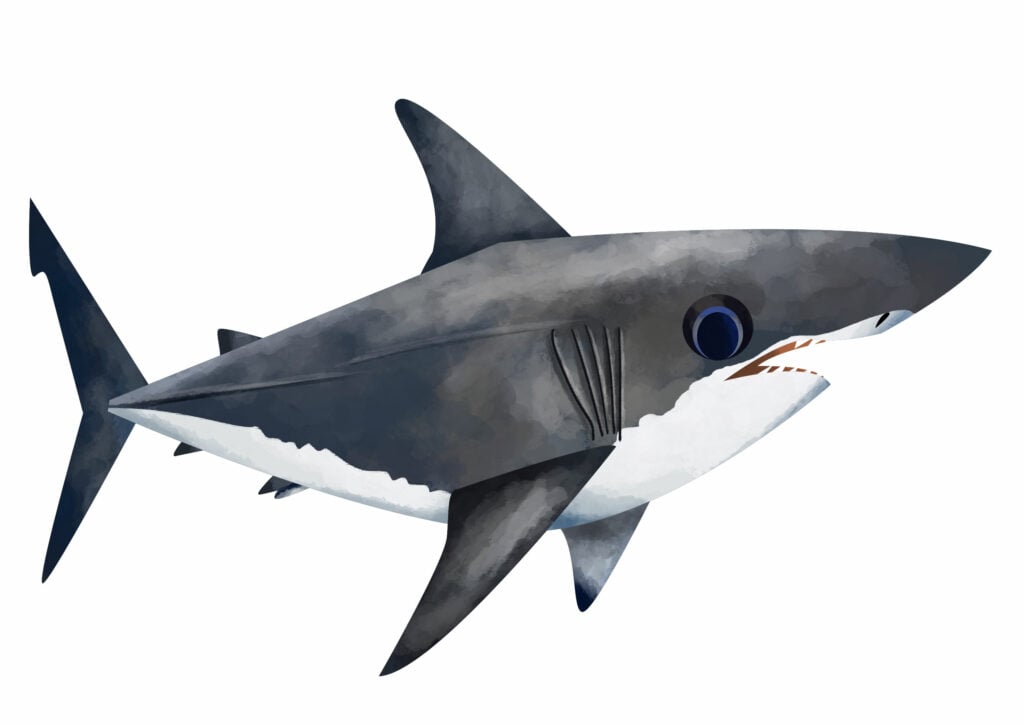

Identification

White sharks are large and torpedo-shaped, with clear countershading – dark grey on top and white underneath. They have large dorsal and pectoral fins, the shape of the dorsal fin being unique to each individual, and they also have a powerful symmetrical tail. Their jaws have distinctive large, triangular teeth with serrated edges, adapted to sawing through whale and sea lion blubber.

Special behaviour

White sharks are incredibly curious, with good eyesight. They will often approach to investigate objects in and above the surface of the water, sticking their head out to take a look in an action known as spy hopping. In South Africa, they also display dramatic breaching behaviour while hunting fur seals; when low light at dawn makes it hard for the seals to see the sharks, they strike at speed and from depth, catching the seals and leaping clear out of the water in the process.

Although not directly a behaviour, white sharks have physiological adaptations in their circulation that allow them to retain body heat and maintain an elevated body temperature. This is referred to as endothermy and leads to higher muscle metabolism, which allows faster swimming to catch agile prey.

Reproduction

White shark reproduction is ovoviviparous, meaning they grow their embryos internally and nourish them from a yolk sack before giving birth to live, independent young. Gestation is estimated at 12 months, following mating via internal fertilisation. Litters may be up to 13 pups, which are born at just over 1 m in length. It is thought that females may take as long as 30 years to reach sexual maturity. New-born white sharks are rarely encountered, but it is assumed that females may migrate to warm temperate and subtropical waters to give birth.

Habitat and geographical range

White sharks are distributed globally in highly productive temperate coastal waters (e.g. South Africa, Mediterranean, east and west USA, Australia), but also migrate seasonally across open ocean.

Diet

White shark diets shift over the course of their development, with larger adults taking an increasing proportion of larger prey items such as sea lions and smaller whales and dolphins. However, white sharks do also feed on various pelagic and coastal fish species, and in some locations (e.g. Australia) these make up the majority of their diet. It has also been suggested that scavenging on large whale carcasses may represent a significant food source.

Threats

Overfishing remains the primary threat to white sharks, which are mainly caught as bycatch in a variety of fisheries globally, including longlines, trawls and gillnets. Ongoing catches have resulted in severe population declines for this species, with an estimated 90% drop reported for some areas (e.g. Australia). There is also targeted catch of white sharks from beach protection programmes in South Africa and Australia.

Relationship with humans

White sharks and people have a complicated relationship. Feared and revered, they are pervasive in popular culture and remain a media favourite. They have been credited with more fatal bites on humans than any other species of shark. This is due primarily to the size, power and feeding behaviour as well as the increased encounter rates it has with humans. Thankfully, such events remain incredibly rare. Meanwhile white sharks continue to be caught in inshore fisheries, exacerbating already substantial declines in their populations. Based on these declines, and their charismatic nature, white sharks were in fact the first shark species to be listed on Appendix II of CITES (alongside the basking shark), restricting international trade in their products (which now mostly focuses on trophies, such as their jaws and large fins).

There is a burgeoning eco-tourism industry around white sharks, with hotspots in South Africa, Mexico and Australia proving incredibly popular with tourists. Done responsibly, these have tremendous value both for inspiring awe for these majestic creatures and for providing a substantial source of revenue to support people’s livelihoods without having to extract any animals. For instance, in Australia, white shark tourism is worth an estimated $8 million annually to the local economy.

Fun facts

White sharks are a highly migratory species. Famously, ‘Nicole’ was tracked migrating more than 10,000 km from South Africa to Australia in under 9 months, before returning to South Africa.

Born more than 1 m in length, white shark pups arrive in the world larger than the average adult shark species.

They have an adaptation called regional endothermy, which allows them to maintain parts of their body above the surrounding water temperature. This is very useful for hunting at speed, which is important for their ambush predation.

References

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, White Shark.

David A. Ebert. et al, 2021, Sharks of the World: A Complete Guide.

Florida Museum, 2018, Carcharodon carcharias

Britannica, 2021, White Shark