scalloped hammerhead shark

Sphyrna lewini

A coastal pelagic, semi-oceanic species, known for forming great schools of up to hundreds of individuals. Like all hammerhead sharks, scalloped hammerheads have an unmistakable elongated head structure, known as a cephalofoil, which is thought to give the shark several advantages including heightened sensory capabilities. Scalloped hammerheads get their name from the distinct notches and indentations found on the front edge of the head. They are also a seasonally migratory species, with females returning to the same inshore nursery grounds to pup.

Identification

Large shark with broad, hammer-shaped head. Central notch with two smaller indentations on the front edge of the head, giving a ‘scalloped’ appearance. Tall dorsal fin, proportionately larger to pectoral fins than most other sharks. Greyish-brown/bronze colouring on the dorsal side; white underside. Pectoral fins have black tips.

Special behaviour

Scalloped hammerheads form very large schools (up to 700 individuals) around seamounts and offshore islands during the day, before splitting off into smaller groups or alone to hunt at night. The reasons behind schooling behaviour remains unclear. These aggregations are thought to be mostly female. For the first few years of life, young sharks stay within the coastal regions in which they were born before heading off elsewhere. Recent studies show these migratory patterns to be highly variable between males and females; females tend to migrate offshore much earlier than males, and return to the same sites to pup once they have reached maturity. However, males leave later in life than females, and where some don’t return, others do. Some males even stay in the same coastal region for their entire life.

Reproduction

Scalloped hammerheads are viviparous, meaning that the developing young is nourished via the placenta, before being born live. Females have an 8- to 12-month gestation period, before giving birth to around 12 to 41 pups in shallow, inshore nursery grounds. Males reach sexual maturity at around 10 years, and females at 13 to 15 years.

Habitat and geographical range

Scalloped hammerheads utilise both coastal and oceanic habitats and can be found in waters ranging from surface level to 1,043 metres deep. They are typically found over continental/insular shelves and nearby deep water, but also frequent close inshore habitats including sheltered bays and estuaries. They have a worldwide distribution in warm temperate and tropical waters, and undertake circumtropical migrations.

Diet description

Scalloped hammerheads are generalist predators, tending to eat whatever is abundant in their area. Their diet can range from bony fishes, like sardines, herring and mackerel, to stingrays and other sharks, and marine invertebrates like squid and crustaceans.

Threats

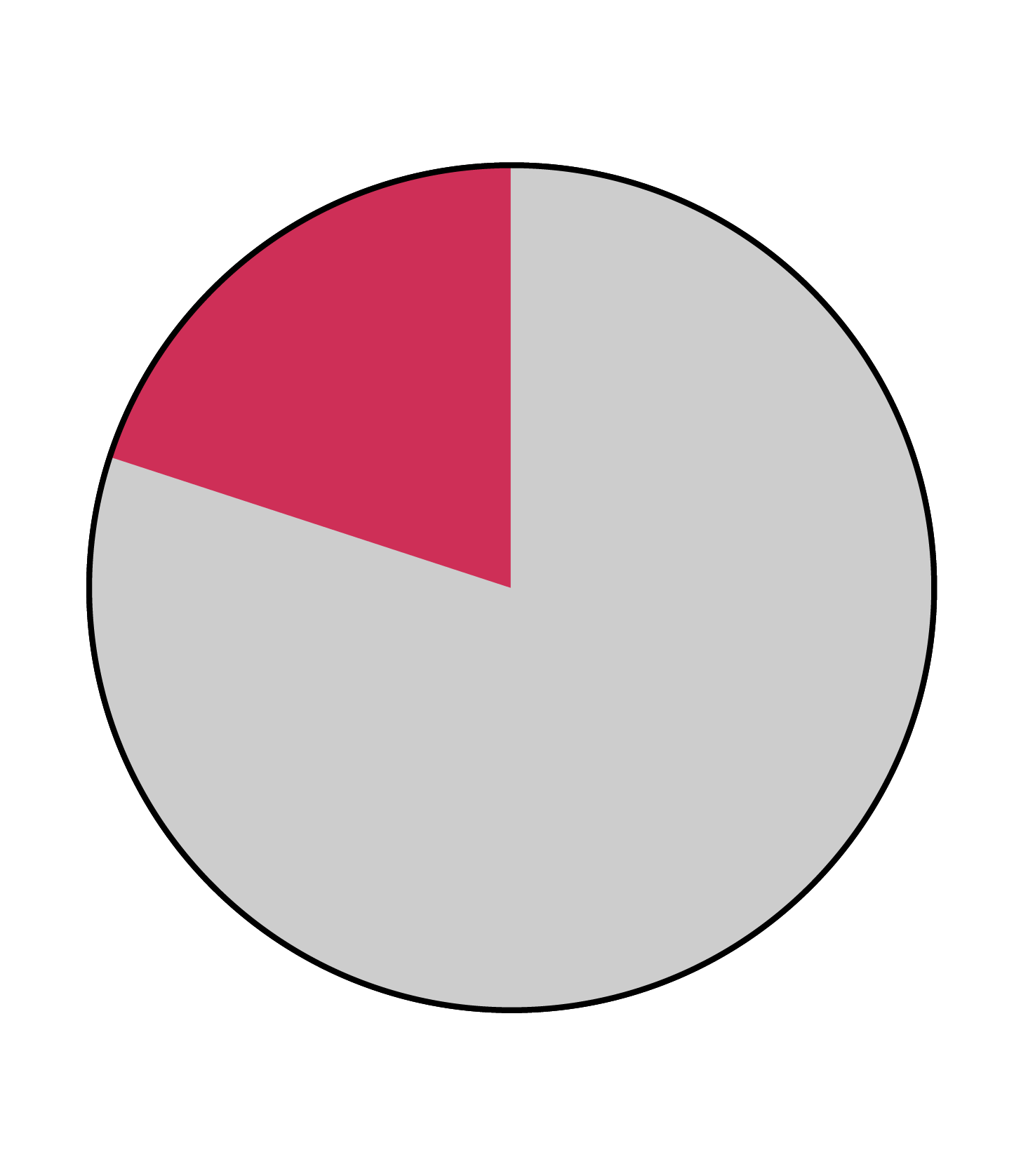

The schooling behaviour of scalloped hammerheads has made them vulnerable to overfishing, which occurs throughout much of their global distribution. Their fins are highly valued in the international fin trade, and by 2015 scalloped hammerhead fins were the third most abundant species identified from genetic analyses in Hong Kong. Globally, their population has declined by more than 80%.

Relationship with humans

According to the International Shark Attack File, there have been 17 unprovoked incidents for the genus Sphyrna worldwide, though none were fatal. Scalloped hammerheads have been reported adopting ‘threat’ postures when approached closely by divers, but are mostly considered a shy species that tends to avoid interaction. Their large aggregations are popular attractions for dive tourism.

Scalloped hammerheads are commercially fished for their meat, hide and fins. Their proximity to inshore areas, tendency to aggregate, and shallow nursery grounds make them particularly accessible to fishing operations.

Fun facts

Scalloped hammerheads have been found to adapt their feeding strategies in response to climate variability! Scientists found evidence of scalloped hammerheads doing this during El Niño and La Niña events, suggesting potential for future adaptation.

The hammer shape of the head, known as a cephalofoil, is thought to have many useful functions. They increase the shark’s field of vision, and provide a greater surface area for electroreceptors, heightening their ‘sixth sense’.

Scalloped hammerheads have been observed using their cephalofoils to pin down stingrays on the seabed!

A recent study suggests scalloped hammerheads sometimes swim on their side, and roll from side to side – a behaviour thought to have evolved for social interaction and to improve swimming efficiency.

The lateral tip of the cephalofoil, or the ‘eye-bulb’, has been shown to function in much the same way as a winglet on an aeroplane and improves hydrodynamics, reducing drag and allowing the shark to turn faster.

References

David A. Ebert et al. 2021. Sharks of the World: A Complete Guide.

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Scalloped Hammerhead Sphyrna lewini

Nalesso, E. et al. 2019. Movements of scalloped hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna lewini) at Cocos Island, Costa Rica and between oceanic islands in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. PloS one, 14(3), p.e0213741.

International Shark Attack File . Global Map.

Estupiñán-Montaño, C. et al. 2021. New insights into the trophic ecology of the scalloped hammerhead shark, Sphyrna lewini, in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean . Environmental Biology of Fishes, 104(12), pp.1611-1627.

Arnés-Urgellés, C. 2021. The Effects of Climatic Variability on the Feeding Ecology of the Scalloped Hammerhead Shark (Sphyrna lewini) in the Tropical Eastern Pacific . Frontiers in Marine Science, p.1829.

Royer, M. 2020. Scalloped hammerhead sharks swim on their side with diel shifts in roll magnitude and periodicity. Animal Biotelemetry, 8(1), pp.1-12.

Taheri, A., On the Hydrodynamic Effects of the Eidonomy of the Hammerhead Shark’s Cephalofoil in the Eye Bulb Region: Winglet-Like Behaviour. Marine Science and Technology Bulletin, 11(1), pp.41-51.