Reef manta ray

Mobula alfredi

Reef manta rays are one of the largest ray species, yet they feed on tiny plankton. They are regularly seen on coastal and oceanic reefs, often pausing at cleaning stations or feeding in large aggregations. Their size and beauty make them a strong draw for tourists, but they face increasing exploitation from trade in their gill rakers.

Identification

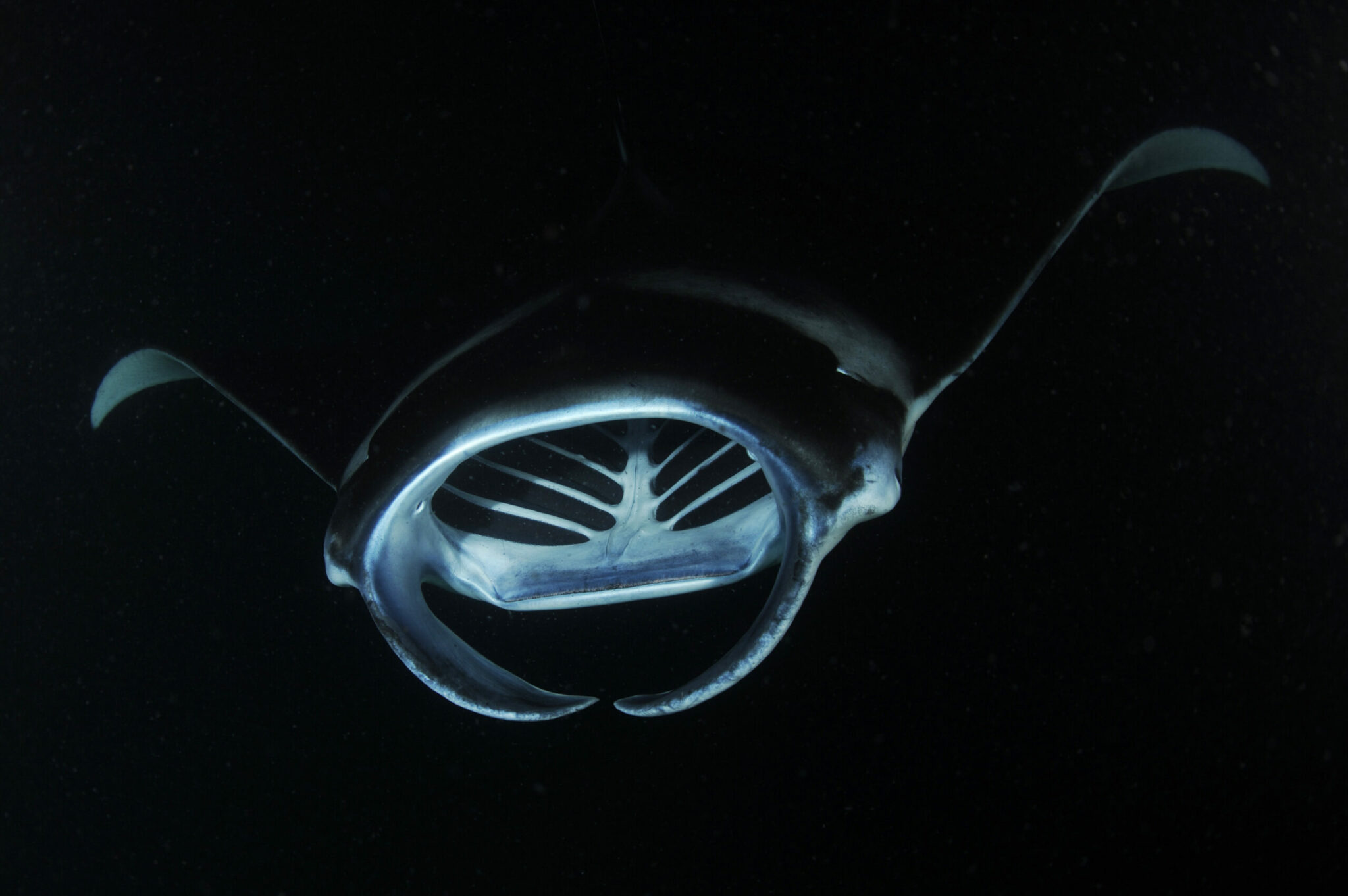

Only recently were reef and giant manta rays separated into different species based on genetic evidence. While both species are predominantly black and diamond-shaped, and have cephalic lobes (appendages either side of their mouth that help funnel water when feeding), the reef manta ray is recognisable through its smaller size and different colouration. Reef manta rays rarely exceed 4 m, whereas giant manta rays can reach 7 m. All manta rays have spots on their underbelly that can be used for individual identification, but in reef manta rays these can be anywhere on their underside (wings and belly), whereas in giant manta rays they are largely restricted to the belly with no spots under the wings. Manta rays also usually have pale grey ‘chevron’ shapes on their backs; in reef mantas these form a ‘Y’ shape and the edges can be quite blurred into the black of the body, whereas in giant mantas they form a more distinct ‘T’ shape. Giant manta rays also have a noticeable lump at the base of their tail, which is a vestigial remnant of their spine; this is absent in reef manta rays.

Special behaviour

Reef manta rays perform a number of interesting behaviours, with the most iconic perhaps being their cyclone feeding. Most famous from Hanifaru in the Maldives, when manta rays congregate in high numbers in dense plankton, they often end up circling around in the patch of food together, forming a large, swirling cyclone of mantas that can be made up of hundreds of individuals. Another striking behaviour is barrel rolling, which they also perform when feeding in high density plankton – to keep feeding in the same spot, they will roll over and over with their mouths wide open to capture as much food as possible. Reef manta rays can also often be seen at cleaning stations on reefs, where they will approach and hover almost motionless to have parasites removed by cleaner wrasse.

Reproduction

Reef manta rays are ovoviviparous, meaning they grow their embryos internally and nourish them from a yolk sack before giving birth to live, independent young. They have one of the slowest rates of reproduction of all sharks and rays, and may only reproduce every four years. Not maturing until 8–17years of age, it means that a reef manta ray may only have 4–7 pups during its lifetime. Pups are born at around 1.4 m in width.

Habitat and geographical range

Reef manta rays have a wide distribution in tropical and subtropical waters of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, but are not recorded in the eastern Pacific. They are generally resident to productive coastal environments, in particular reefs and atolls. In many locations they exhibit strong daily patterns in their habitat use, whereby they may occupy cleaning stations during the day and feed offshore and deeper at night. In certain locations, such as in Seychelles and the Maldives, the tidal cycle can also play a significant role in aggregating plankton and thereby the movements of the reef mantas.

Diet

As with the largest sharks, these large rays feed only on tiny plankton and small fish. They will swim with their mouths wide open and their cephalic fins extended to funnel water through their mouths and over their gills, where their specialised gill rakers will filter out the plankton. In particularly productive plankton patches they can be seen performing barrel rolls while feeding in the same spot.

Threats

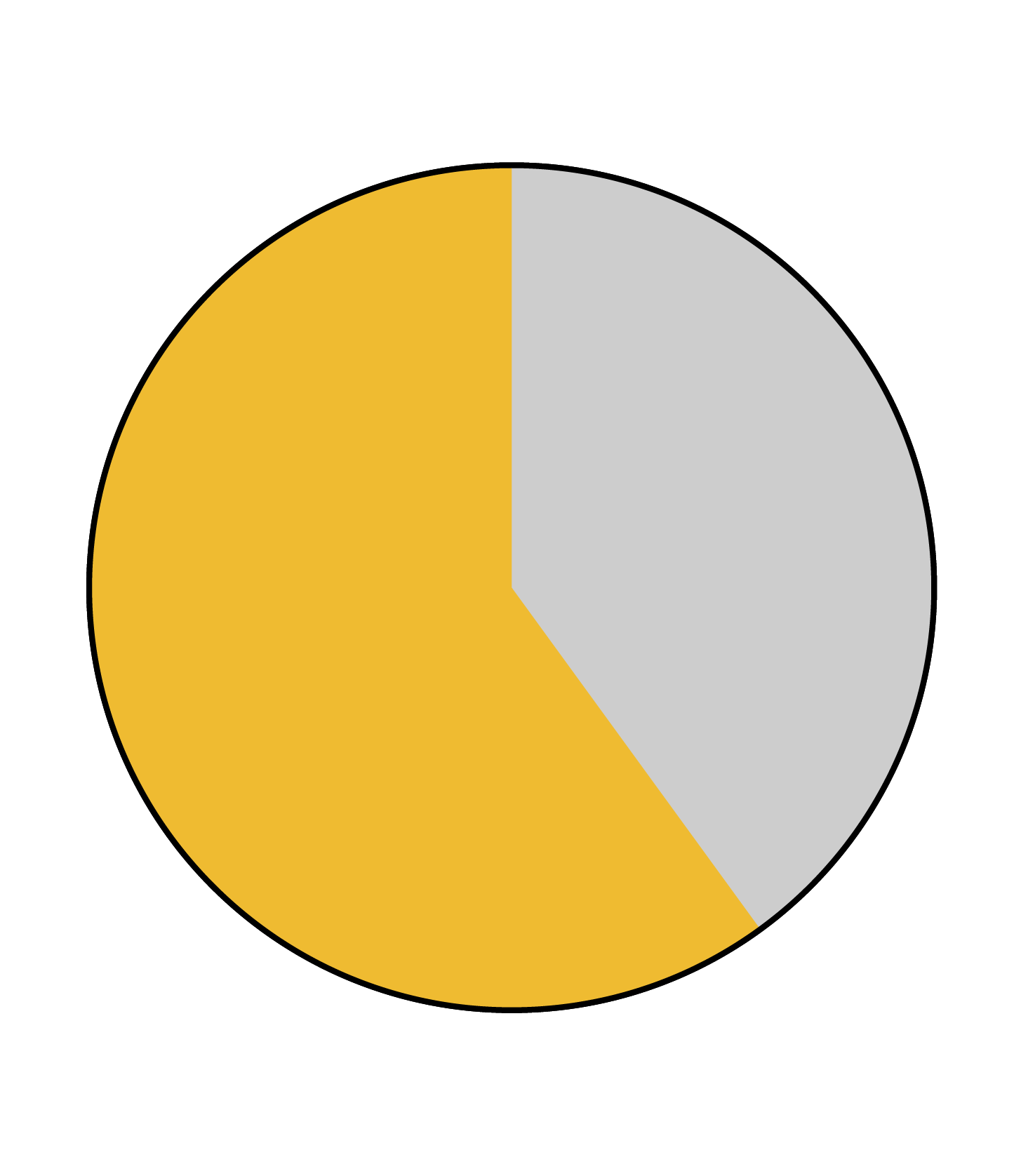

As with most sharks and rays, the greatest threat to reef manta rays is overfishing. They are widely caught in commercial and artisanal fisheries, and are particularly susceptible to purse-seine and gillnet fisheries. They are used for their meat and oil, but increasingly for their gill plates, especially in Asian markets where the gill plates are marketed as a traditional medicine despite not being present as a remedy in traditional literature. They are also susceptible to vessel strikes, and entanglement in nets and moorings. Their incredibly slow reproduction makes them vulnerable to rapid depletion from overfishing, exacerbating their exploitation and contributing to concerning declines in their population (up to 49% worldwide, but more severe in certain locations). Consequently, reef manta rays are categorised as Vulnerable by the IUCN, and have been listed on Appendix II of CITES to restrict their international trade.

Relationship with humans

Reef manta rays have a conflicted relationship with people as they are both highly exploited for their products and highly revered for their majestic beauty. Demand continues to rise, especially for their gill plates, but increasingly there is also an appetite amongst tourists for encounters with them. In particular, for scuba divers, experiences with reef manta rays are highly sought after due to their size and grace, in combination with the opportunity to encounter them feeding in large numbers. Just as for the giant manta rays, there are certain places (e.g. Maldives) where ecotourism operations thrive off them while providing alternative, more sustainable livelihoods.

Fun facts:

- Reef manta rays may only produce seven pups in their entire life.

- In areas of highly concentrated plankton, hundreds of mantas may aggregate and cyclone feed, where the group spirals around in a tight circle.

- Until recently, reef manta rays were considered to be of the same species as giant manta rays.

- They will gracefully swim over coral reefs and hang almost motionless as cleaner wrasse remove small parasites from their skin.