Pacific cownose ray

Rhinoptera steindachneri

Pacific cownose rays are migratory and often seen travelling in large groups . Their name comes from the unusual shape of their rostrum, which looks like that of a cow. They are the most common batoid species landed by fisheries in the Gulf of California and Baja Sur, Mexico. Their tendency to aggregate and hang around in shallow water makes them vulnerable to overfishing.

Identification

Characteristic ‘diamond’ shaped body, typical of all rays, with a whip-like tail. Their rostrum is the basis for its name; two pectoral fins divide the head into two, with a centre crease and indented notch which gives it a cow-like appearance. They are dark brown in colour with a distinct gold/bronze tint, reflected by their other common name, the golden cownose ray.

Special Behaviour

Pacific cownose rays travel in schools. When near the surface, they are known to breach, leaping clean out of the water.

Reproduction

Pacific cownose rays reproduce via matrotrophic viviparity, meaning that the young receives additional nourishment from the mother through uterine milk (also known as histotroph) before being born live. It is thought that pacific cownose rays reproduce annually and only give birth to one pup per year.

Habitat and geographical range

Pacific cownose rays prefer soft bottom habitats, like sand and mud, where they can dig around for food. They are a shallow water species, occurring in depths of 0 to 65 metres on the continental shelf and inshore. They are found in the eastern Pacific Ocean, from northern Mexico to northern Peru.

Diet description

Pacific cownose rays are bottom feeders, eating crustaceans and molluscs. They crush the hard shells of their prey between two flattened tooth plates.

Threats

Pacific cownose rays are one of the most common batoid species caught by artisanal gillnet fisheries in the Gulf of California, and are also regularly caught as by-catch by demersal shrimp and hake trawls. They are retained for their meat, and sometimes used as bait. Their tendency to travel in schools and preference for shallow waters makes them vulnerable to overfishing.

Relationship with humans

Like many others in the family Myliobatidae – the eagle and manta rays – Pacific cownose rays have tail spines they can use for defence. But they are largely considered not dangerous to humans. Humans consume the meat from Pacific cownose rays, and sometimes use them as bait.

Conservation

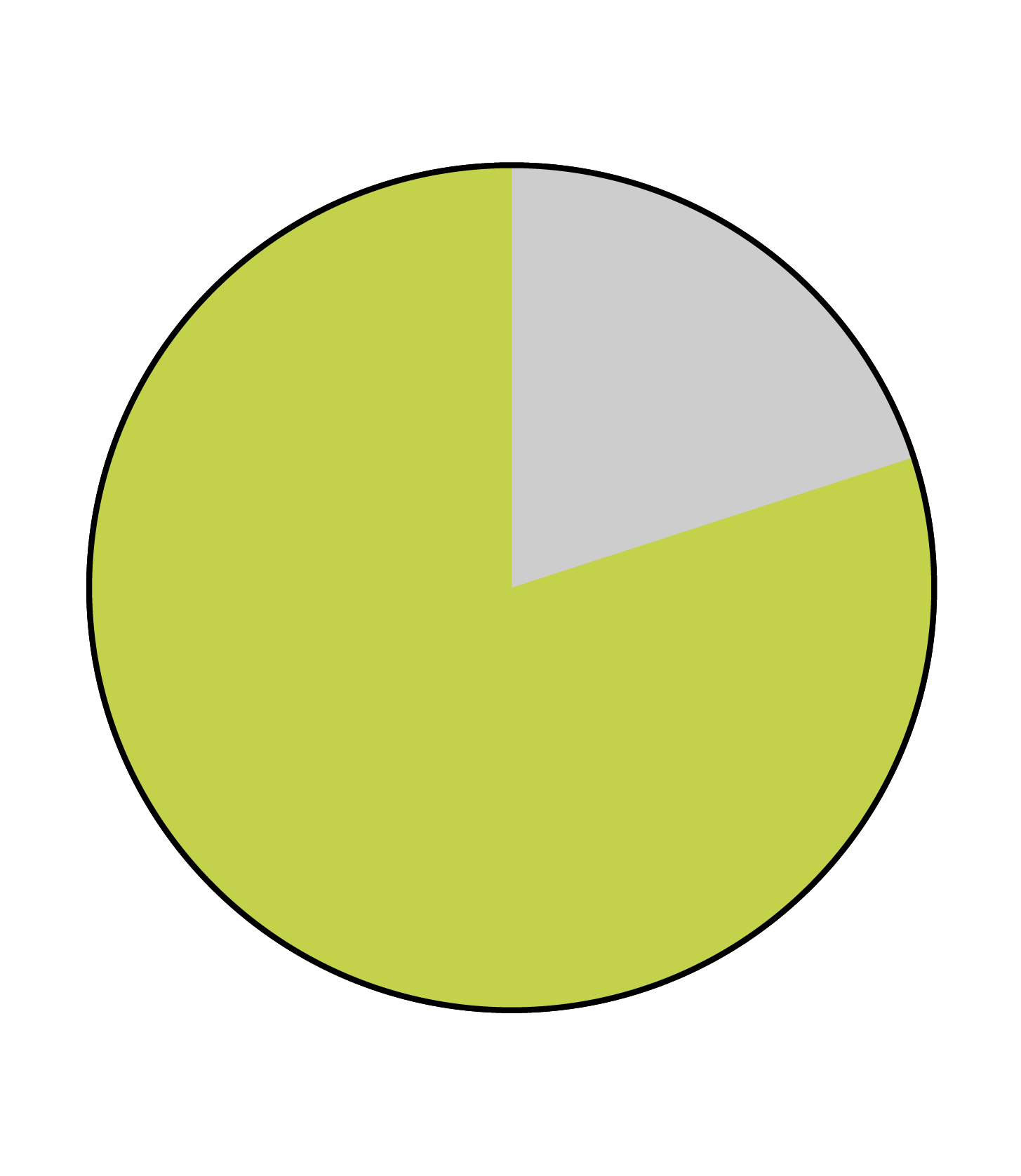

There are no species-specific measures in place to protect Pacific cownose rays, but there are some conservation measures for elasmobranchs more broadly throughout their range. For example, Colombia has a ban on shrimp trawl fisheries – which may catch sharks and rays as by-catch – between January to March, and has set by-catch limits (the number of sharks and rays caught accidentally) to 35%. The Galápagos Marine Reserve prohibits industrial fishing altogether. However, artisanal gillnet fisheries are increasing and are largely unmanaged throughout the southern parts of the Pacific cownose ray’s range, and stronger enforcement of existing protective measures is needed.

Fun facts

- Pacific cownose rays are known to leap clean out of the water!

- They can adjust to habitats with widely varying salinities, like estuaries, intertidal marshes and coastal lagoons.

- They are known to cruise the seafloor using a ‘fluttering’ motion. They detect buried prey by smell, touch and electroreception.

- Once something tasty is located, they will use their rostrum to dig into the sand, making a depression 40cm deep, before using their modified pectoral fins to create suction – essentially hoovering food out of the ground!

- As a bottom feeder, it sometimes finds unwanted silt and sand in its mouth, which it has to expel from its gills.

References

IUCN Red List. Pacific cownose ray: Rhinoptera steindachneri

Burgos et al., 2018, Reproductive strategy of the Pacific cownose ray Rhinoptera steindachneri in the southern Gulf of California. Marine and Freshwater research.