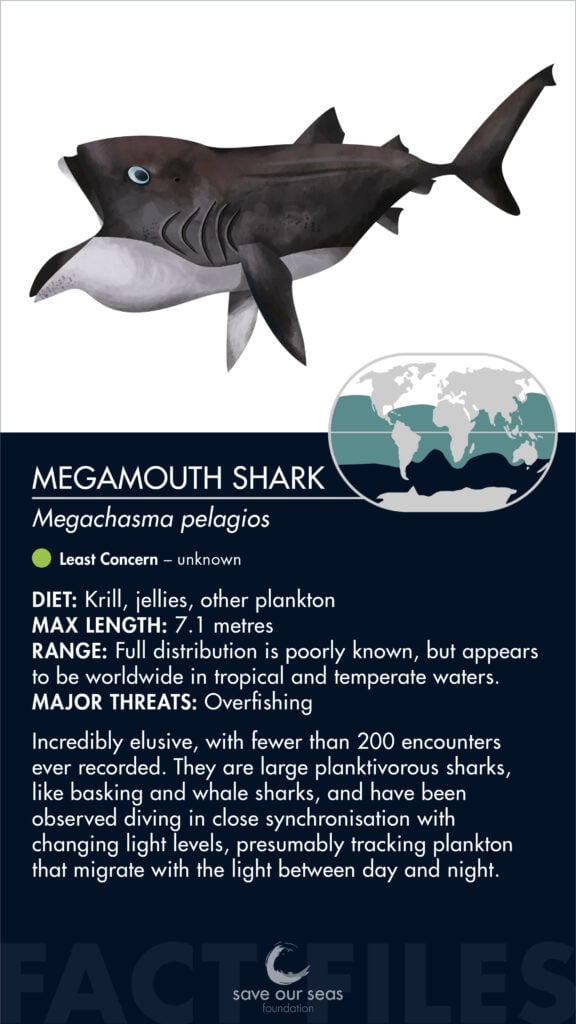

Megamouth Shark

Megachasma pelagios

Megamouth sharks are incredibly elusive, with fewer than 200 encounters ever recorded. They are large, planktivorous sharks like basking and whale sharks, and have been observed to dive in close synchronisation with changing light levels – presumably tracking plankton that migrate with the light between day and night.

Identification

Megamouths are easily identified by their bulbous head and broad mouth that extends behind the eyes. They are large (more than 7 m, but potentially up to 9 m) and dark grey in colour across their back with a white underbelly. Compared to basking and whale sharks they have relatively small dorsal fins, but the upper caudal fin is quite elongated, a bit like a thresher shark.

Special behaviour

Megamouths may perform what is known as diel vertical migrations, where they spend the day in relatively shallow water, then migrate to deeper depths as the sun sets to remain there during the night. They then return to the shallows as the sun rises. This is presumably in response to the distribution of their planktonic prey, which also switches between the shallows and depths by day and night. It has been suggested from their mouth shape that they may be able to perform engulfment feeding, similar to humpback whales.

Reproduction

Little is known of megamouth reproduction, as no pregnant or neonate specimens have ever been found. All that is known is that the embryos resemble those of mackerel sharks such as white sharks, and so the megamouth could similarly be ovoviviparous. Available data suggest they mature at around 5 m in length.

Habitat and geographical range

Given that very few megamouths have ever been seen, their full distribution is poorly known, but it appears to be worldwide in tropical and temperate waters (although most specimens have come from Japan, Taiwan and the Philippines in the Pacific). They appear to occur largely in pelagic waters, from the surface to depths of 1,500 m but have also been reported in shallow, coastal waters.

Diet

Megamouths feed mainly on krill, jellies and other plankton, and it is thought they may be able to perform engulfment feeding like humpback whales. As with basking sharks, they have gill rakers to filter their prey from the water and also one of the lowest densities of electroreceptors among sharks, suggesting they may rely less on electroreception for feeding than other shark species. Megamouths have a bright white band on their upper jaw that is only visible when the mouth is open – some believe this may act as a lure to planktonic prey in dark conditions.

Threats

The primary threat to megamouths is presumed to be overfishing, but they are only known to be taken occasionally as incidental bycatch in a range of coastal and pelagic fisheries. A significant proportion of recorded megamouth specimens are as bycatch in driftnet fisheries for sharptail mola off Taiwan, and increasing reports suggest they may be experiencing elevated exploitation. Although its conservation status requires more information to be properly assessed, based on the very low number of known captures the megamouth shark is currently considered to be Least Concern by the IUCN.

Relationship with humans

Megamouths are enigmatic and hold broad public intrigue, with photos or footage of them often making the news. Early specimens have been preserved for display in aquaria, but otherwise they are kept for their meat when caught. They have likely been encountered many more times than known, but are probably discarded or released by fishermen due to their large size. The first confirmed megamouth shark was reported in 1976 when it became entangled in the anchor of a US Navy vessel in Hawaii.

Fun facts:

Megamouth sharks are vertical migrators, moving up and down through the water column to follow the movements of their prey.

They have a bright white band on their upper jaw that is only visible when the mouth is open – some believe this may act as a lure to planktonic prey in dark conditions.

The first confirmed megamouth shark was reported in 1976 when it became entangled in the anchor of a US Navy vessel in Hawaii.

They are rarely encountered and fewer than 200 specimens have ever been recorded.

References

David A. Ebert. et al, 2021, Sharks of the World: A Complete Guide.

IUCN, 2021, Megamouth Shark

Florida Museum, 2019, Megachasma pelagios