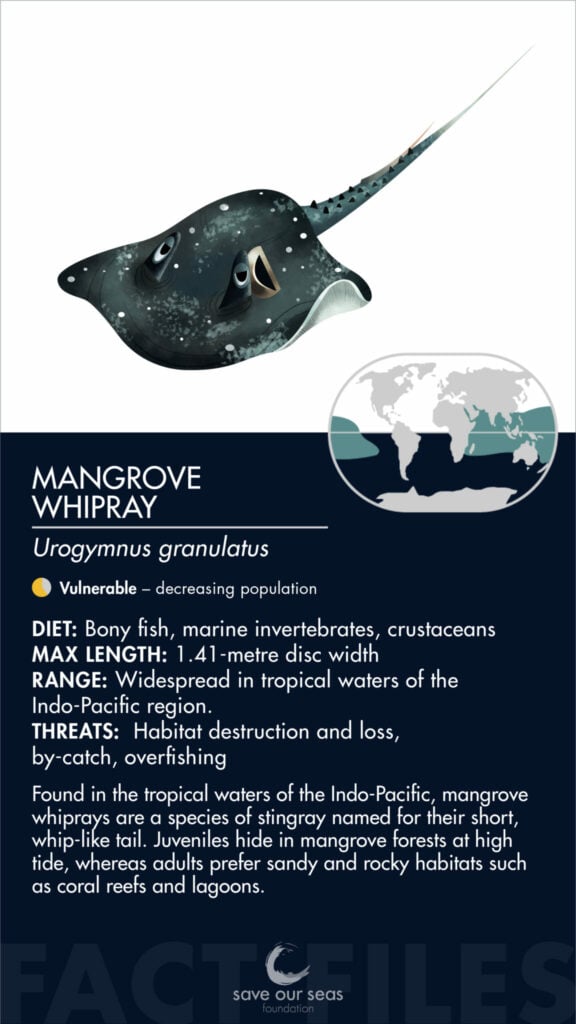

Mangrove whipray

Urogymnus granulatus

Not much is known about mangrove whiprays, their movements, and how they use their habitat. Although they have a wide distribution in the Indo-Pacific, they are considered an uncommon species. It is known that juveniles seek refuge from predators in the towering roots of mangrove forests. Widespread destruction of this vital habitat is a major threat to mangrove whiprays.

Identification

Mangrove whiprays have a large, oval-shaped body (approx. 1.41-metre disc width), of very dark grey or brown covered with white ‘freckles’. The tail is short and whip-like, and is coloured white beyond the stinging spine.

Special behaviour

Mangrove whiprays are solitary animals. Juveniles hide out in shallow, tidal habitats such as mangroves and estuaries to avoid predators and feed mainly on small crustaceans, including crabs and prawns. Adults are found in a greater variety of habitats, preferring sandy or rocky habitats like lagoons, coral reefs and sand flats. They are bottom-dwellers, and hunt along the seabed.

Reproduction

Very little is known about the reproduction and life history of mangrove whiprays. They are viviparous with histotrophy, which means that the developing foetus receives nourishment from uterine secretions, known as ‘histroph’ or ‘uterine milk’. Litter size and age of sexual maturity is unknown.

Habitat and geographical range

Mangrove whiprays are typically found in tropical inshore waters including mangroves, coral reefs, estuaries and sandflats. Some adults move offshore, and have been found at depths of 85 metres, but in general individuals prefer shallower waters. They have a widespread distribution in the Indo-Pacific region, from the Red Sea to Northern Australia and Micronesia.

Diet description

Mangrove whiprays feed on a variety of bottom-dwelling animals, including benthic bony fishes (e.g. rabbitfishes, blennies, gobies and wrasses), crabs, octopuses, worms and bivalve molluscs.

Threats

Widespread loss and destruction of mangrove systems is a major threat to the species, as this habitat is central to the survival of juvenile mangrove whiprays. In addition, the species’ preference for shallow, inshore habitat makes it vulnerable to artisanal fishing pressure. By-catch is also a threat to mangrove whiprays. For example, the commercial gillnet fishery in Indonesia targeting wedgefishes in the Arafura Sea accidentally catches mangrove whiprays, which are retained and sold. It is thought that this has contributed to the decline of the Southeast Asian population.

Relationship with humans

The mangrove whipray is a stingray. Its tail has a stinging spine that can injure humans. However, mangrove whiprays are typically shy and will likely swim away if approached.

Mangrove whiprays are threatened by a range of human activities, from habitat loss and destruction to fisheries and by-catch. There are protected areas for mangrove whiprays, such as the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (GBRMP) in Australia, and some gear modifications for fisheries designed to reduce by-catch. However there are few of these measures outside of Australia.

Fun facts

The mangrove whipray’s movements are influenced by the tide and time of day. Juveniles prefer mangrove areas at high tides to reduce predation risk, and tend to be more active during the day. Adults however forage at night, and rest during the day either half-buried in sand or on top of coral heads.

The mangrove whipray's dark colouration is actually due to a thick layer of mucus; without it, mangrove whiprays are a lighter grey.

They were first described in 1883 by zoologist John Macleay. He gave it the Latin species name ‘granulata’ because of the small white ‘granules’, or speckles, that cover the whipray’s dorsal side.

They use their ‘sixth sense’ – electroreception – to find buried prey.

References

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Mangrove Whipray Urogymnus granulatus

White et al. 2006. Economically important sharks and rays of Indonesia. Canberra, Australia: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research

Davy et al. 2015. Movement patterns and habitat use of juvenile mangrove whiprays (Himantura granulata). Marine and Freshwater Research, 66, pp. 481-492

Martins et al. 2020. Tidal–diel patterns of movement, activity and habitat use by juvenile mangrove whiprays using towed-float GPS telemetry. Marine and Freshwater Research, 72(4), pp. 534-541

Kanno et al. 2019. Stationary video monitoring reveals habitat use of stingrays in mangroves. Marine Ecology Progress Series 621, pp. 155–168.