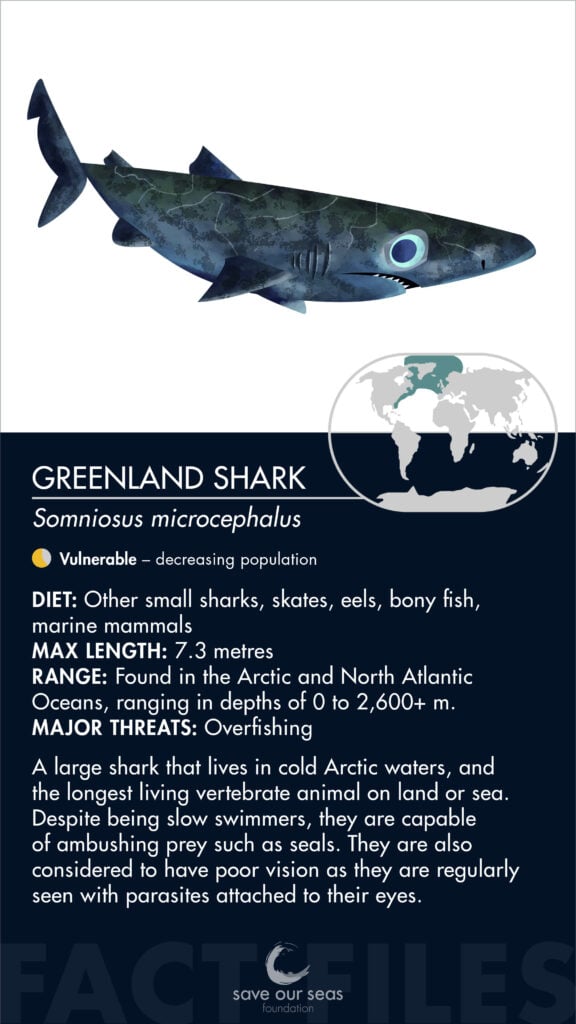

Greenland shark

Somniosus microcephalus

Greenland sharks live in cold Arctic waters, and are the longest living vertebrate animals on land or sea. Although they are one of the slowest swimming animals on record, they are capable of ambushing prey such as seals. Because they are regularly seen with parasites attached to their eyes, they are considered to have poor vision.

Identification

Greenland sharks have large, heavy bodies with a mottled grey colouration that gives them a slug-like look. They have short rounded snouts, and their fins are also disproportionately small. They have narrow mouths and small eyes, which often have parasites attached and can be opaque in appearance.

Special behaviour

More a biological feature than a behaviour, but these sharks are the longest living vertebrate animal of any kind. It is possible they may live for up to 400 years, but most likely around 270. Despite their slow pace of life, they appear to be active hunters of marine mammals – seals are known to form part of their diet, assumed by past researchers to be from scavenging. However, stomach temperature readings have revealed warm spikes, suggesting that some prey are still warm and likely caught alive.

Reproduction

Greenland sharks are ovoviviparous, meaning they grow their embryos internally and nourish them from a yolk sack before giving birth to live, independent young. Up to 10 pups can be produced at a time, with varied sizes at birth of 0.4–1 m.

Habitat and geographical range

Greenland sharks are found in the Arctic and North Atlantic Oceans, ranging in depths of 0–2,600 +m and temperatures of 1–12˚C. However, there are limited sightings as far south as France and Portugal, but genetic evidence cautions that the true range may be more restricted, with some of the extended range attributable to hybridisation with Pacific sleeper sharks.

Diet

Greenland sharks have a varied diet that includes other sharks, skates, eels, herring and a variety of other fish. They also feed on marine mammals such as seals, which had until recently been presumed to be entirely from scavenging due to their slow swimming. However, stomach temperature readings have revealed warm spikes, suggesting that some prey are still warm, and likely caught alive. Individual stomachs have been found to contain an entire reindeer, parts of a horse and even a polar bear, which is the largest land predator.

Threats

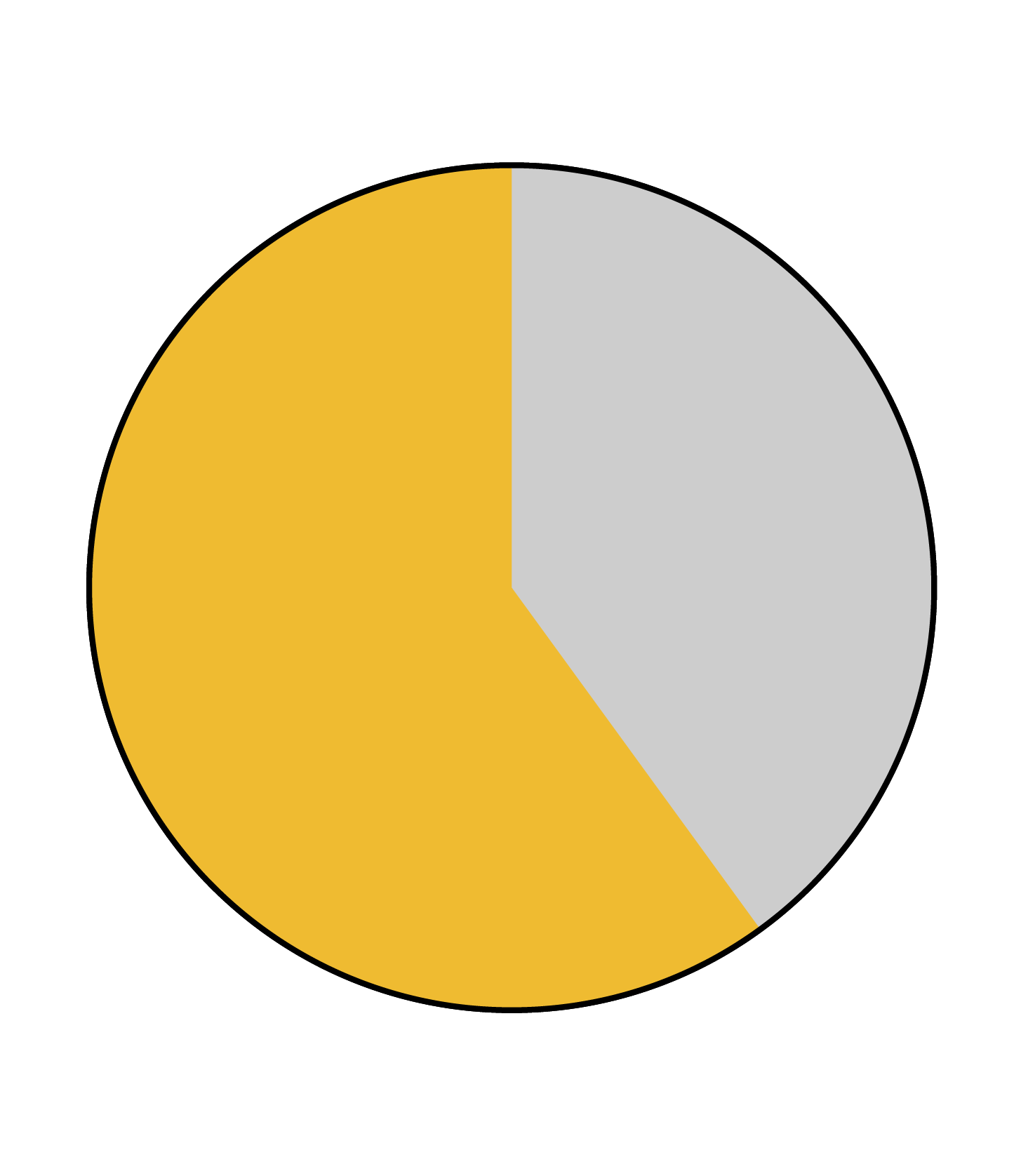

The primary threat for Greenland sharks is overfishing. For many centuries they were targeted commercially for their liver oil, but more recently fishing has been limited to artisanal fisheries in Greenland and Iceland. Since the 1960s, they have also been threatened as bycatch in industrial trawl, longline and gillnet fisheries from Canada and the USA. Incidence of persecution has too been reported, where their tails were cut off and returned to the water, in response perhaps to damaged fishing gear. Climate change, through the reduction of sea ice, is expected to cause habitat loss and provide increased access to fisheries. Although very difficult to estimate, Greenland shark populations are thought to have declined by 30–49%, and they are listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN.

Relationship with humans

In addition to the long history of liver-oil use, their meat is also regularly used in various communities. Although the flesh is actually poisonous if consumed raw due to the high content of urea and trimethylamine oxide, it can be consumed safely if properly prepared. For instance in Iceland fermented Greenland shark, or hákarl, is considered a national dish, and is eaten after a long process of fermentation and drying. If consumed without proper preparation it can cause intestinal and neurological issues that present similar to drunkenness. As a result, people who are drunk are sometimes referred to as ‘shark sick’.

There is no confirmed risk of Greenland sharks to people, but an anecdotal report from 1859 in Pond Inlet, Canada, does claim that a caught Greenland shark was found to contain a human leg in its stomach. Although never investigated or proven, such an incident likely relates to scavenging, as Greenland sharks tend to occupy waters too cold for swimmers.

Fun facts

- Greenland sharks are the longest living vertebrate at 270, and possibly even 400, years old!

- They have very poor eyesight, and are possibly even blind, as most individuals have parasites living on their eyes.

- Although slow swimmers, there is evidence of them hunting marine mammals, reindeer and polar bears!

References

David A. Ebert. et al, 2021, Sharks of the World: A Complete Guide.

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Greenland Shark: Somniosus microcephalus

Florida Museum, 2018, Somniosus microcephalus

Oceana, Greenland Shark: Somniosus microcephalus

Britannica, Greenland Shark: Somniosus microcephalus