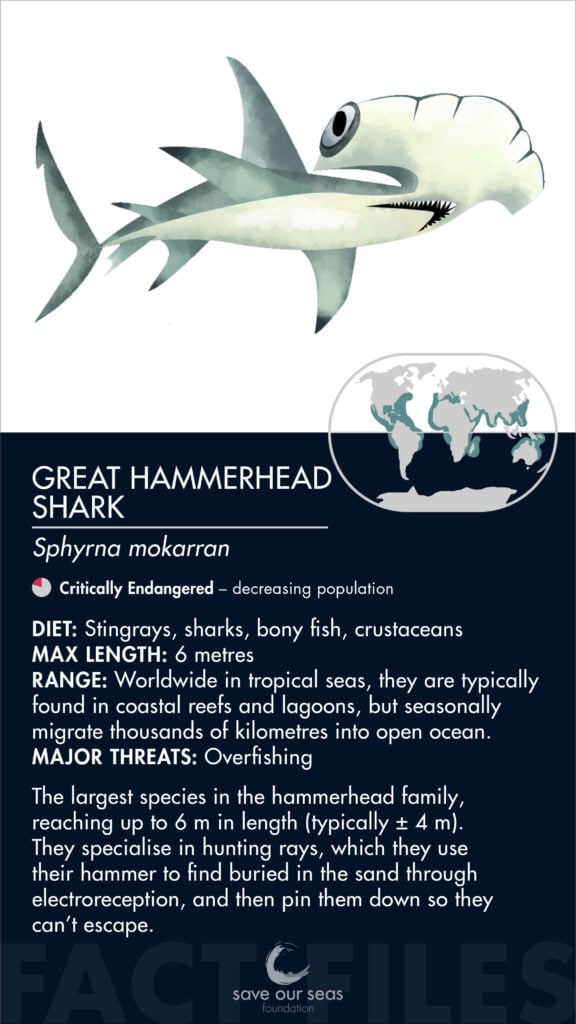

Great hammerhead shark

Sphyrna mokarran

Great hammerheads are the largest species in the hammerhead family, reaching up to 6 m in length (typically ± 4 m). They specialise in hunting rays, using their hammer to find them buried in the sand through electroreception and then pin them down so they can’t escape.

Identification

Great hammerheads are the largest of the hammerheads and clearly identifiable by their hammer-shaped head (or cephalofoil) that has a single notch at the centre, and their disproportionally large first dorsal fin. Their fins also appear more sickle-shaped than other hammerhead sharks. They are pale grey in colour.

Special behaviour

Great hammerheads are specialised ray hunters, and have been observed using their hammer to pin down and immobilise rays they have found on the seafloor. They are also regularly observed swimming almost on their sides; wild great hammerheads spend 90% of their time at roll angles of 50–75. Tilting like this means their large first dorsal can provide additional lift, but hydrodynamic modelling has revealed that this position also saves them 10% in drag and the cost of movement.

Reproduction

Great hammerheads are viviparous, meaning they have a placenta and give birth to live young. After a gestation period of approximately 11 months, a female may produce up to 55 pups that each measure 0.5–0.7 m in length. Great hammerheads grow faster than many other sharks of their size, and tend to mature earlier at 5–9 years of age.

Habitat and geographical range

Worldwide in tropical seas and typically found in coastal reefs and lagoons, but also known to seasonally migrate thousands of kilometres into open ocean.

Diet

Great hammerheads have a relatively broad diet, including stingrays, other sharks, bony fish, and crustaceans, but they do tend to have a particular preference for stingrays. Their hammer (or cephalofoil) helps them find rays buried in the sand through electroreception, and is used to pin them down so they can’t escape.

Threats

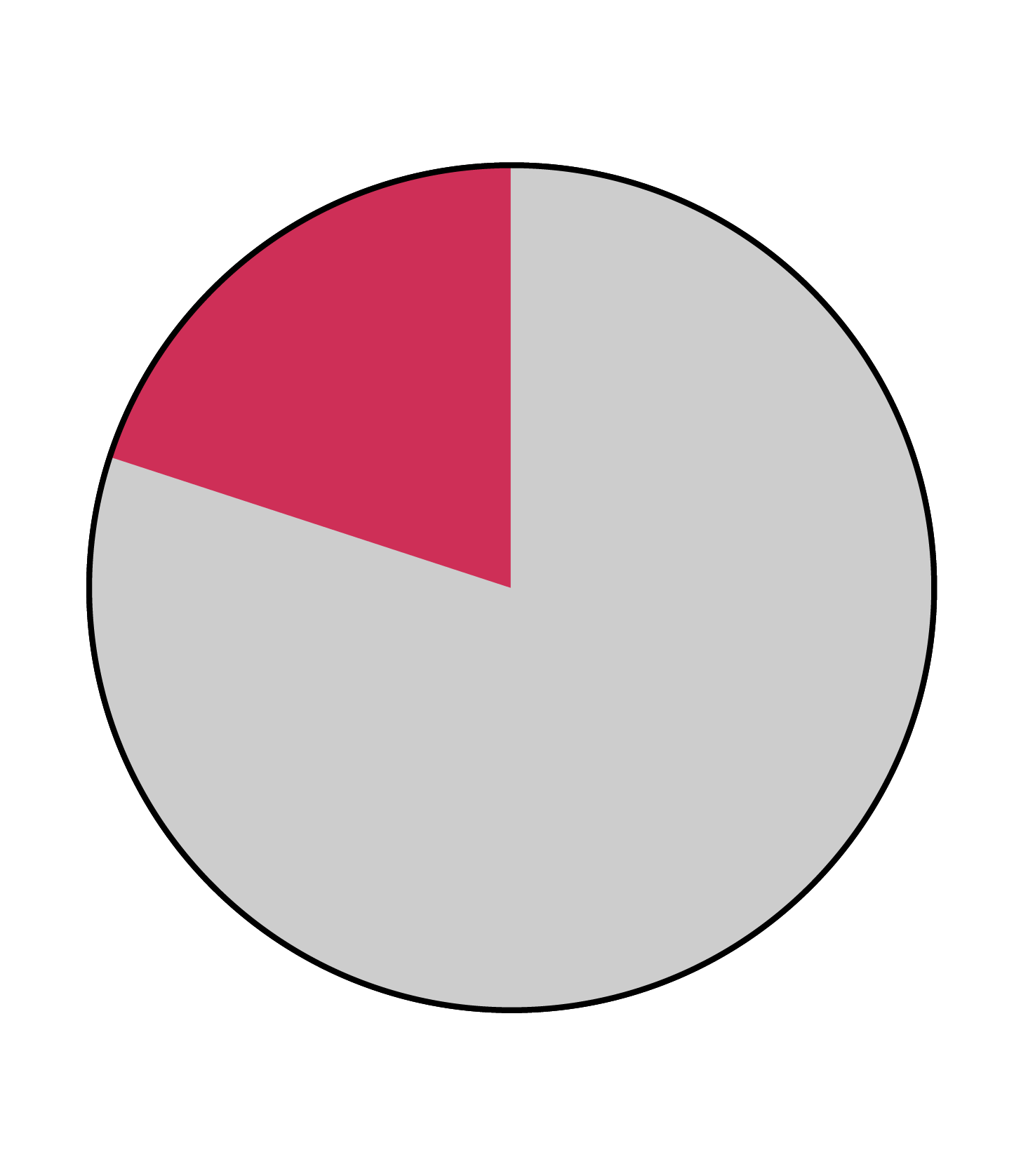

Great hammerheads are Critically Engendered due to their severe declines as a result of overfishing. They are caught globally both as target and bycatch in longline, purse seine and gillnet fisheries. They are also considered valuable trophy catches in recreational fisheries, and are often caught in beach protection programmes that target large sharks.

Relationship with humans

Great hammerheads have been valuable to fisheries globally for their meat and oil, but given their size (particularly of their impressive first dorsal) their fins are also highly sought after for display. They are similarly popular with recreational fishermen. Unfortunately, great hammerheads are fragile and have exceptionally high at-vessel mortality, meaning that even catch and release fisheries pose a significant threat to them. Overall declines of more than 70% mean this species is now listed on Appendix II of CITES, which restricts their international trade. However, their charismatic nature also means they are highly sought after for encounters by tourists, and despite their severe declines there are some locations where they can be encountered reliably. The Bahamas in particular has a number of dive operations specifically targeting great hammerheads, providing alternative and more sustainable livelihoods to overfishing.

Fun facts

Great hammerheads are the largest hammerhead species, reaching lengths that are comparable to white sharks – up to 6 m!

They spend most of their time swimming on their side, which helps increase lift and reduce drag, together reducing the energetic costs of swimming.

References

David A. Ebert. et al, 2021, Sharks of the World: A Complete Guide.

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Great Hammerhead: Sphyrna mokarran

Florida Museum, 2018, Sphyrna mokarran