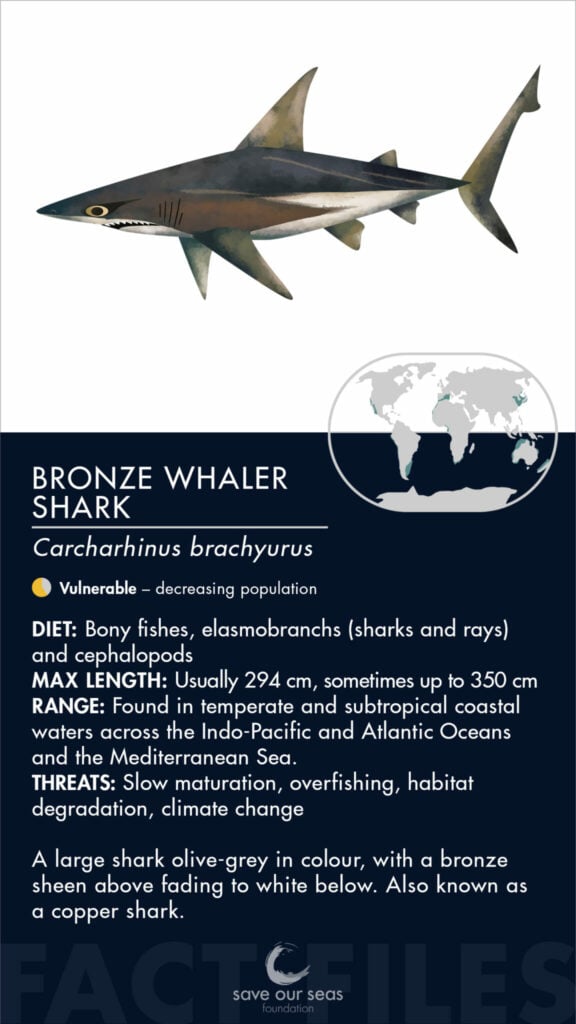

Bronze whaler shark

Carcharhinus brachyurus

A large shark olive-grey in colour, with a bronze sheen above fading to white below, the bronze whaler (or copper) shark is typical of shallow coasts across a patchily distributed range in temperate waters. In South Africa, the movement patterns of these sharks have been linked to those of sardines during winter months, and sardines were overwhelmingly recorded as the predominant prey species in bronze whaler sharks during the annual sardine run period.

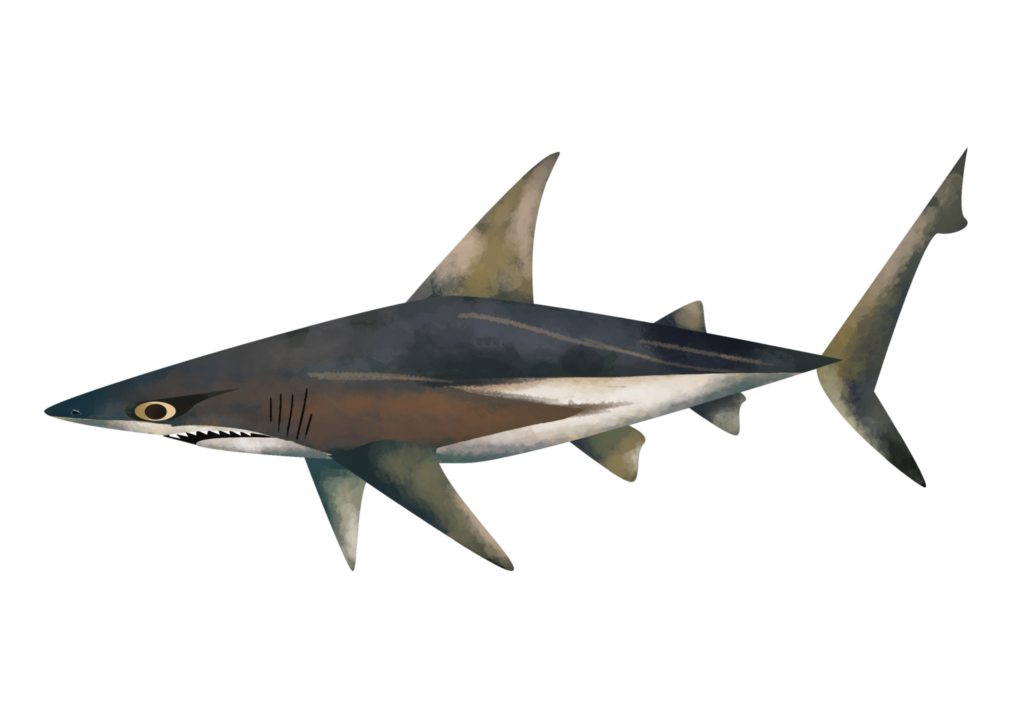

IDENTIFICATION

A large shark with a broad, blunt snout and no interdorsal ridge (the raised strip between the first and rear dorsal fins). Long pectoral fins with small dorsal fins and short rear tips, the bronze whaler shark is olive-grey in colour, blending from bronze above to white below. Fin tips are dusky in colour, but not obviously marked. The bronze whaler shark is often confused with the dusky shark (Carcharhinus obscurus), blacktip shark (Carcharhinus limbatus), sandbar shark (Carcharhinus plumbeus), and spinner shark (Carcharhinus brevipinna). However, it is distinguished by the narrow, bent cusps on its upper teeth, the absence of any obvious body markings, and the lack of an interdorsal ridge.

SPECIAL BEHAVIOUR

In southern African waters, bronze whaler sharks peak in abundance in temperate regions during the summer months and in subtropical waters during the winter months. These movement patterns have been linked to the annual migration of sardines, which form the primary prey of these sharks across size classes. Unusually for a species in the Family Carcharhinidae, bronze whaler sharks are typical of temperate rather than tropical waters. Some populations appear to be regionally isolated, with little mixing or genetic exchange between them.

REPRODUCTION

Bronze whaler sharks are viviparous (they give birth to live young, which are nurtured in-utero by a yolk sac placenta) and may have litters of between 13 to 24 pups in alternating years. Gestation is around one year long. Pups are born at between 59 – 70 cm length. Records suggest that males reach sexual maturity anywhere from 13 to 17 years old (200 – 235 cm length), and females reach sexual maturity from 16 to 20 years old (less than 245 cm).

HABITAT AND GEOGRAPHICAL RANGE

Bronze whaler sharks are typical of inshore coastal and continental shelf habitats, to a maximum of around 100 m depth. These are cosmopolitan sharks found in warm temperate and subtropical waters patchily distributed across the Indo-Pacific, Atlantic and Mediterranean. Coastal habitats have been shown to be important for bronze whaler sharks, with juveniles showing site fidelity in South Australian seagrass meadows, possible nursery habitats on the South African Southern Cape coast, and predictable seasonal peaks in abundance and changes in movement patterns that are often linked to the occurrence of prey such as shoaling sardines.

DIET DESCRIPTION

Smaller-sized bronze whaler sharks have been recorded eating predominantly small, shoaling fish like sardines and invertebrate cephalopods like squid (Loligo v. reynaudii). In larger sharks, the proportion of small sharks and rays like shortnose spurdog, St Joseph shark and lesser guitarfish increases. Larger sharks also ate octopus, which suggests these older individuals are feeding on benthic (seafloor-dwelling) animals. Bronze whaler sharks of all sizes are associated with the annual sardine run on South Africa’s east coast, where their primary prey is the sardine.

THREATS

Bronze whaler sharks are long-lived, very slow-growing, and late to reach sexual maturity. These traits make the species vulnerable to overexploitation. Throughout its range, the bronze whaler is fished commercially and recreationally. As large, coastal predators that use nearshore habitats (especially in their early stages of life), they are also vulnerable to coastal development and the degradation of inshore habitats. In some areas, their status is considered Least Concern (Australia) and the rate of fishing sustainable. However, as scientists in South Africa have pointed out, their slow growth, cross-border movements and preference for coastal areas place these sharks at risk where their management is not regionally-informed.

RELATIONSHIP WITH HUMANS

Bronze whaler sharks are caught by anglers for recreation and by fishers for food. They are occasionally aggressive with divers, and may be considered potentially harmful to swimmers and divers.

CONSERVATION

Bronze whaler sharks are listed on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Appendix II, which regulates international trade in shark products that would otherwise threaten their survival. Classified as Vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) on their Red List of Threatened Species, the possibility that bronze whaler shark stocks are distinct from one another across their global distribution means that management of their populations needs to be both regionally-informed and cooperative where wider movement patterns have been observed. The IUCN recommends that, in the absence of monitoring plans and harvesting limits in many regions, national catch limits, regional monitoring and local research needs to be increased for the species.

FUN FACTS

Bronze whalers are well known for following the annual sardine run off South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal coast where they have been photographed and filmed hunting around the famous sardine ‘bait balls’.

Juvenile bronze whaler sharks show ‘site fidelity’, returning annually (for up to 4 years) to the same shallow seagrass meadows in Gulf St Vincent, South Australia where scientists have been tracking them.

Scientists have shown that the presence of bronze whaler sharks in some waters depends on a variety of environmental factors, with peaks in shark numbers linked to the season, water temperature, wind speed, and moon illumination.

The South Coast of South Africa might be an important bronze whaler shark nursery. Of the sharks scientists have tagged there, more than 93% were juveniles.

References

Benavides, M.T., Feldheim, K.A., Duffy, C.A., Wintner, S., Braccini, J.M., Boomer, J., Huveneers, C., Rogers, P., Mangel, J.C., Alfaro-Shigueto, J. and Cartamil, D.P., 2011. Phylogeography of the copper shark (Carcharhinus brachyurus) in the southern hemisphere: implications for the conservation of a coastal apex predator. Marine and Freshwater Research, 62(7), pp.861-869.

Cliff, G., and Dudley, S.F.J., 1992. Sharks caught in the protective gill nets off Natal, South Africa. 6. The copper shark Carcharhinus brachyurus (Günther), South African Journal of Marine Science, 12(1), pp. 663-674, DOI: 10.2989/02577619209504731.

Drew, M., Rogers, P. and Huveneers, C., 2016. Slow life-history traits of a neritic predator, the bronze whaler (Carcharhinus brachyurus). Marine and Freshwater Research, 68(3), pp.461-472.

Drew, M., Rogers, P., Lloyd, M. and Huveneers, C., 2019. Seasonal occurrence and site fidelity of juvenile bronze whalers (Carcharhinus brachyurus) in a temperate inverse estuary. Marine Biology, 166(5), p.56. Florida Museum. Discover Fishes. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/carcharhinus-brachyurus/

Huveneers, C., Rigby, C.L., Dicken, M., Pacoureau, N. & Derrick, D., 2020. Carcharhinus brachyurus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T41741A2954522. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T41741A2954522.en. Accessed on 26 April 2024.

Kellett, M.D., 2021. Habitat use and trophic ecology of bronze whaler sharks (Carcharhinus brachyurus) in New Zealand (MSc dissertation, The University of Waikato).

Rogers, T.D., Kock, A.A., Jordaan, G.L., Mann, B.Q., Naude, V.N. and O’Riain, M.J., 2022. Movements and growth rates of bronze whaler sharks (Carcharhinus brachyurus) in southern Africa. Marine and Freshwater Research, 73(12), pp.1450-1464.

Smale, M.J, 1991. Occurrence and feeding of three shark species, Carcharhinus brachyurus, C. obscurus and Sphyrna zygaena, on the Eastern Cape coast of South Africa, South African Journal of Marine Science, 11(1), pp. 31-42, DOI: 10.2989/025776191784287808.

Walter, J.P and Ebert, D.A., 1991. Preliminary estimates of age of the bronze whaler Carcharhinus brachyurus (Chondrichthyes: Carcharhinidae) from southern Africa, with a review of some life history parameters, South African Journal of Marine Science, 10:1, 37 44, DOI: 10.2989/02577619109504617.