Orca predation on white sharks

Show notes

What happens when two top ocean predators collide? This was a question that PhD candidate and white shark expert Alison Towner was faced with six years ago, when the subjects of her thesis started to wash up on shore with unusual, but fatal, injuries. Fast forward to 2022, and Alison has just led her second publication on the predation of white sharks by orcas in South Africa, a behaviour that has never been documented until now. In this episode, Isla chatted to Alison about her findings, why we think orca are only now starting to show interest in white sharks, and the potential effects of predation by orca on not just white sharks as a species but the entire ecosystem…

We start by learning about Alison’s most memorable ocean experience (04.01). For Alison, it’s all about observing one of the world’s most impressive predators in its natural habitat in the company of researchers from all over the world. Her passion for sharks stems from her late father’s love for large predatory fish and his time spent in South Africa writing and angling (06.19). This drove her to study marine biology at university and then into a job as a wildlife guide and biologist for cage-diving ecotourism operations in South Africa (08.07). She actually got the job with Marine Dynamics by telling them that, in a boat full of men, they needed a woman on board!

Her work in white shark tourism planted the seeds for her future scientific endeavours (11.10). Spending time at sea, observing white sharks every day and learning from the local knowledge around Gansbaai was instrumental in forming the research questions for her masters and then later her PhD. We talk about the questions she set out to answer with her PhD, which focussed on the movement ecology of white sharks, with funding from the Save Our Seas Foundation (13.06). She has used acoustic telemetry to understand how white sharks are using Gansbaai and also how they interacted with cage diving vessels – or at least, that’s what her project first focussed on before some other visitors to the area threw a spanner in the works…

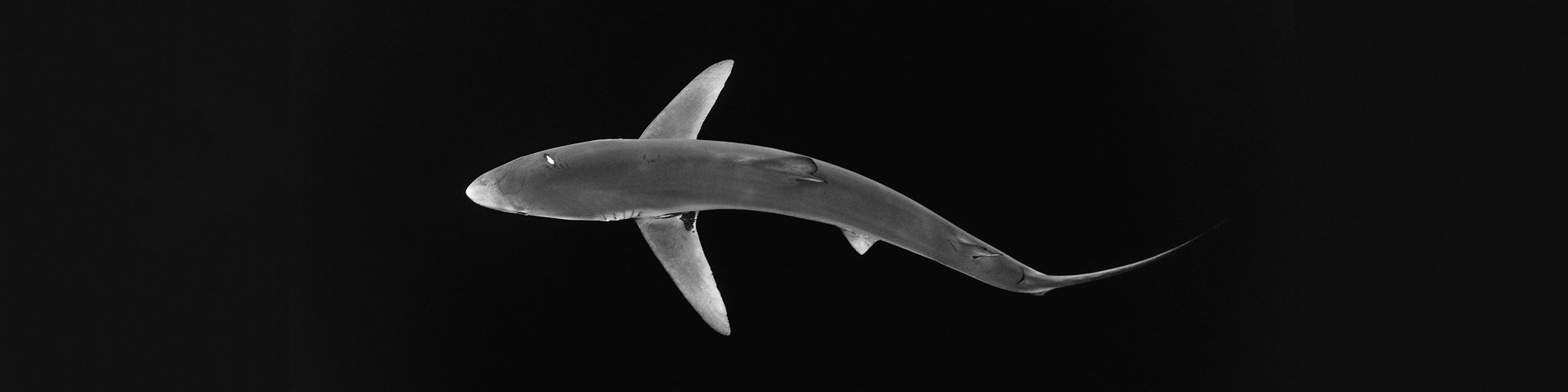

Before getting stuck into the subject of orcas, Isla and Alison discuss Gansbaai and its importance to white sharks (15.53). She describes it as the perfect pitstop – an abundance of food and the right environmental conditions that provide sustenance and shelter on the sharks’ migratory routes. Her masters research showed that different ages and sexes use the environment differently. Large females tend to be offshore, and juveniles and males are more coastal (17.24). We also talk about some of the adaptations that white sharks have to allow them to be the optimal ocean predator, including regional endothermy, the ability to conserve heat and raise the temperature of certain body parts (19.27). This has allowed white sharks to have a wider range and keep up with highly mobile prey, like seals. Alison also tells us a little about her research on white shark behaviour around cage-diving boats, which indicated that the sharks soon got bored and tended to spend less and less time around them (25.08). She believes that this is because the reward they get – in the form of chum – isn’t enough to keep them coming back. Of course, this is when the operations are properly managed and adhere to the strict codes of conduct around cage-diving, which you should definitely look into before you choose a tourism operator – if it’s something that takes your fancy!

One thing that is influencing white shark movements and behaviour in South Africa is their top ocean rival: orcas. Alison is among the first scientists to discover that orcas predate on white sharks – something she never expected to become a part of her PhD research (30.03)! In 2017, the bodies of white sharks began to wash ashore, each one with a unique injury. The liver had been removed with almost surgical precision. This coincided with increased sightings of two orcas in the area, named Port and Starboard (31.28). Over the space of a few years, white sharks began to leave the areas in which they had once been common and where the orcas had been reliably sighted (33.00). This is known as ‘displacement’ and was thought to be in response to the orcas hunting and killing sharks. However, they didn’t have direct evidence of a predation event – until this year, when it was captured on camera from the air (44.53). For the first time, orcas have been documented hunting and killing white sharks (46.33). Alison’s most recent publication analyses this footage and suggests that cultural transmission has occurred; in other words, Port and Starboard have taught other orcas how to make a meal out of white sharks.

We talk about why orcas are hunting white sharks now and in such great numbers (36.36). Although there is evidence of other orcas hunting sharks elsewhere (39.22) it is unusual for them to come so close inshore and kill so many. Alison and other scientists believe that this is possibly the result of overfishing – the orca aren’t getting what they need offshore, so they have moved into coastal bays where there is a plentiful supply of white sharks (38.00). This means it’s a multi-layered issue with no easy solution.

We also discuss the ripple effects of this new behaviour throughout the marine ecosystem in South Africa and Gansbaai specifically (41.08). Because white sharks are apex predators, as they are taken out or displaced from their usual hangouts, it has wide-ranging impacts on other species. The behaviour of cape fur seals, for example, has changed – without the fear of being eaten, they are ranging farther afield and have turned their attention to a breeding colony of Critically Endangered African penguins on the adjacent island (42.40).

So how do you solve this problem and help conserve white sharks? As Alison says, blaming the orca isn’t the right place to start – rather, we need to address the multitude of anthropogenic issues that also affect them. And the activities that have pushed the two ocean titans closer in the first place (48.29).

About our guest

ALISON TOWNER

Alison graduated from UK’S Bangor University in 2006 with a BSc Hons degree in Marine biology and moved to Gansbaai, South Africa, in January 2007, where she has remained on site studying white sharks for the last 15 years. She completed and published her MSc on white sharks through the University of Cape Town and continues her research on the species, focusing on telemetry. She is currently about to complete her PhD at Rhodes University, which examines the novel interactions between killer whales and white sharks in South Africa.

Read Alison’s work online:

Direct observation of killer whales predating on white sharks and evidence of a flight response