Lisa Boonzaier on the world’s marine protected areas

Lisa Boonzaier is the SOSF Conservation Media Unit’s content editor. She has also recently led a study that provides a global overview of protection of the world’s oceans. This is the most up-to-date and comprehensive study of this nature and will provide a new baseline for all future assessments. She carried out her research during her Master’s degree at the University of British Columbia, supervised by Professor Daniel Pauly. We asked her a few questions about where we are in terms of global marine protection.

What are the international targets for ocean protection?

There are a few global targets for ocean protection that have been set to try and encourage countries to designate more protected areas. The most well known is one established in 2010 by the Convention on Biological Diversity, or CBD, which set out the target that 10% of the ocean should be protected by 2020. Although this seems like a great idea, I should point out that – unfortunately – this was not the first time they had laid out a 10% target. 10% was first set as a target by the CBD in 2006 and the deadline was 2012, but when 2010 came along and we were nowhere close to 10%, they extended the deadline.

More recently, last year in fact, the World Parks Congress set a target for 30% of the ocean to be protected from all extractive activities, including all fishing. Which is much bigger than the CBD goal, but there is no timeline for it.

What can a marine protected area offer in terms of protecting our oceans and making them more sustainable?

Marine protected areas can help to protect a defined area of the ocean from disturbance. Some marine protected areas prohibit certain types of fishing, others protect against all types of extractive activity, and still others are no-go areas that you can’t even enter unless it’s for science. So there are many different types of protection. We know that the more protected an area is, the greater the benefits to biodiversity.

However, there are some things that marine protected areas can’t protect against. Things like warmer water, pollution and ocean acidification. But we hope that with more protection for the ocean, there will be greater resilience to this type of change.

How do we define marine protected area?

You would think this would be a simple answer! But really there are so many types of marine protected areas.

The most widely accepted and used definition of a marine protected area comes from the CBD – which is also the convention that set the 10% target for protection.

For a place to be considered a marine protected area by the CBD it needs to be clearly defined, it needs to be long-term and it needs to have the primary objective of nature conservation. Also, the protected area must be effectively managed in such a way that it achieves the long-term conservation of nature.

Dolphins ride the bough wave ahead of a research vessel at Chagos Marine Reserve. © Photo by David Tickler

When was the last study to assess the extent of global MPAs undertaken and what were their findings?

In 2006, Louisa Wood created the database of marine protected areas that provided the foundation for my study. She estimated that around 0.65% of the ocean was protected at that time, and less than 0.1% was within areas protected from extractive activities – also called ‘no-take’ marine protected areas, because you are not allowed to take anything from them.

More recently, another study led by Mark Spalding and based on a different database of marine protected areas estimated that 2.3% of the global ocean was protected. They didn’t estimate the no-take marine protected area.

How have we progressed since then?

So my new study, which I co-authored with Daniel Pauly, shows that since then, we have made progress, but not enough. By the end of 2014, around 4% of the ocean was protected. I say ‘around 4%’ because this is not a definite number; marine protected areas are being created – and degazetted, unfortunately – all the time, but this is our best guess. So this is significantly up from the earlier estimates of 0.65% in 2006 and 2.3% in 2012.

And of that 4%, only around one-sixth, or 0.5% of the oceans are in no-take marine protected areas. This is a five-fold increase from 2006, which is great, but a paltry amount nonetheless.

One third of the global ocean's no-take area is contained within the Chagos Marine Reserve. © Photo by David Tickler

How did you collect your data for this study?

I wish I could say I was able to travel the world and go and visit the 6,000 marine protected areas in the database I used! But in reality updating Louisa’s database involved a lot of desk work: researching online, sending out emails, communicating with local experts, reading management plans.

The declaration of a marine protected area, does not necessarily mean it will be effective or enforced, so what is the value of knowing how much of our oceans are theoretically protected if it does not add up to actual conservation?

Good question! And you’re right, simply declaring a marine protected area is not enough to mean that there will be benefits for nature conservation. There are many factors that need to be in place to ensure that, like sufficient funding, skilled staff, clear objectives and enforceable legislation, but designation is the first step – and an essential – step

Also, measuring those additional factors is difficult and we don’t really know how best to do that yet. But it is something that scientists are working on.

And on the other hand, looking at global marine protected area gives us a clear, understandable number that we can use to assess progress (even if it is at the most basic level) and motivate further action – which we need.

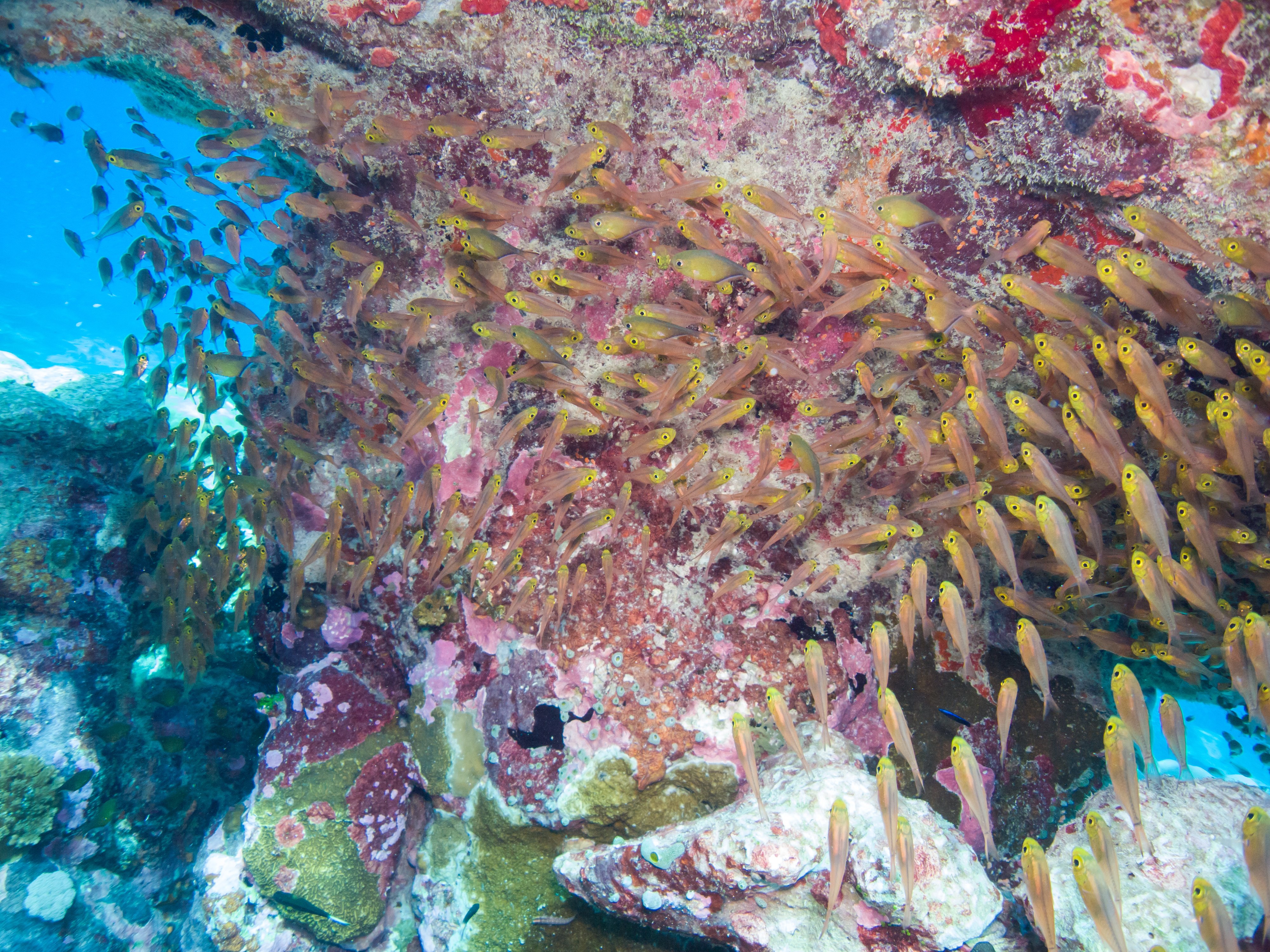

Pygmy sweepers schooling under a table coral that is covered with crustose algae at Chagos Marine Reserve. © Photo by David Tickler

Do you think it is feasible that we will reach global targets?

I think it is feasible, but we need to see a lot more of the ocean protected between now and 2020, and I think it’s only with large-scale marine protected areas, that we have any hope. To reach even the lowest target of 10%, we’d need to protect more than double what’s protected up to now. To put that into perspective, we’d need to protect an area equivalent to more than 16 times the biggest marine protected area declared to date.

What were the major marine protected areas you looked at in your study and have any new ones been declared since then?

Two very big marine protected areas, each more than 1 million km2, were declared during 2014. Big marine protected areas like this dominate global statistics because they make up a disproportionate part of the ocean’s protected area.

One was declared around New Caledonia, a French territory in the Pacific Ocean. This is the biggest marine protected area declared to date. The other represents an expansion of the United States’ Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument. It was expanded from 200,000 km2 to almost 1.27 million km2. That’s almost the size of Peru!

Lisa’s paper is freely available here.